A retired judge of the High Court of Lagos State, Justice Isiaka Isola Oluwa is dead. He was 102 years old.

Justice Oluwa, who died at his Ilupeju residence in Lagos on Saturday, was laid to rest at Atan Cemetery, Yaba, at 4pm, according to Islamic rites.

Justice Oluwa will be remembered as the judge who sentenced Lagos socialite, Alhaji Jimoh Isola, popularly known as Ejigbadero, to death for murder of a farmer, Raji Oba, over a land dispute in 1975.

Ejigbadero was arguably one of the famous people in Lagos of 1960s and 1970s. He was rich. He was streetwise. He was known. He was connected. He was the darling of musicians of the day. One of the surest ways to launch a musical career then was to sing about Ejigbadero. Yusuf Olatunji (Baba Legba) devoted substantial part of his Volume 19 to sing his praises and Ebenezer Obey and his Inter Reformers Band, celebrated him in his 1974 album.

If Nigeria was not under military rule in 1970s, Jimoh Ishola could have contested and won an elective political position. He was that famous.

Though Ejigbadero was not born in Lagos, he became the unofficial Lord Mayor of Lagos metropolis. Jimoh hailed from Oja-Oba Quarters in Ibadan, Oyo State. He came with his uncle to Lagos as a young man to learn a vocation. On his arrival Lagos, he quickly graduated from an apprentice to a nail company owner.

Nail manufacturing was however not Ishola Ejigbadero’s only vocation. Over the years, he had acquired reputation as a dealer in landed properties. Ejigbadero was known to the police. He was familiar to the judges as a perennial litigant. And one curious thing about his court appearances is that he was never a plaintiff.

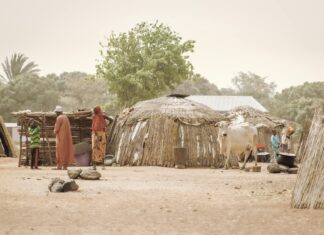

According to him, he had purchased all the plots of land around Alimosho-Egbeda villages from one Olubunmi family. Ejigbadero also claimed that he had compensated all those whose land he acquired in the area since 1970 and therefore, no one had any business staying on the pieces of land.

But the family of Raji Oba, one of the residents in the area, thought otherwise. And each time Ejigbadero came to the village with thugs to harass the villagers, the Raji Oba family always resisted, claiming that they would not quit the land.

That was the state of things on the night of August 22, 1975. The moon was quite bright and Raji Oba and his wife, Sabitiyu, decided to relax in front of their house. Suddenly, there were gunshots and Raji Oba started groaning from the bullet wounds.

Immediately, Sabitiyu saw Ejigbadero, along with four other people running into the bush. But Ejigbadero was a good strategist. He did his homework very well before executing his plan. He worked out a good alibi that could have extricated him from the tangled web.

Just as he was firing shots at Raji Oba in Alimosho village, music was blaring at his home where there was a party to celebrate his daughter’s naming ceremony. So, immediately after shooting Raji Oba, Ejigbadero went back to the party, attending to visitors who could attest to the fact that he never at any time left the venue of the party for another place.

All the same, being the prime suspect, Ejigbadero was arrested on January 7, 1976.

In his autobiography titled: ‘A Life in Motion: Reminiscence of a Jurist at 100 years,’ late Justice Oluwa said he believed the celebrated murder case influenced the enactment of the Land Use Decree, now known as Land Use Act, by the military government of General Olusegun Obasanjo in 1978.

Justice Oluwa’s account of the case as contained in the book is as follows:

“As a judge, many controversial cases were brought before me that made headlines in the newspapers. One of such cases was the criminal case of Ejigbadero. I was assigned the Ejigbadero case by the Honourable Chief Justice of Lagos State in 1975. The case attracted a lot of public interest because it involved a well-known socialite, one Jimoh Ishola who was the executive chairman of Jimsol Nigeria Ltd, a nail manufacturing company in Lagos. Ishola was better known by his alias, Ejigbadero.

“He had his factory at the Matori Industrial Estate, and lived in Mushin with his large family, including his four wives. Apart from being an industrialist, Ejigbadero was a well-known land speculator and property dealer. What brought him to my court was a case of murder when he was accused of killing one Raji Oba.

“As a judge, one must remain impartial about every case and not allow public sentiments to affect one’s judgement. Evidence must be presented and witnesses must be led to support or disprove every evidence.

“I would like to dwell more on the Ejigbadero case, which I believe generated a lot of public interest and in the long run, had more impact on the policy formulation of land matters both at the Federal level and at the State level.

“The Lagos State Director of Public Prosecution led the prosecution and built an impregnable fortress of evidence against Ejigbadero. Sometime in 1974, Ejigbadero had gone to Alimosho village on the outskirt of Lagos, to clear a piece of land which he claimed he had bought. He was challenged by some of the villagers who disputed Ejigbadero’s claim to ownership.

“The land which Ejigbadero decided to clear for a new building construction, contained cocoa, kolanut and some other cash crops. The villagers accused Ejigbadero of an attempt to seize their land illegally. Ejigbadero had come to the land with some boys alleged by the villagers to be thugs. Ejigbadero claimed they were his workers.

“When the villagers did not allow them to work, Ejigbadero retreated after the first encounter. He returned several times thereafter and this led to clashes during which some of the villagers, including Raji Oba, were wounded. The police at Alimosho intervened and tried to bring peace but to no avail. No one was charged to court at that stage and the police also did not make any arrest.

“On August 22, 1975, Raji Oba was relaxing in front of his house at Alimosho. It was around 7.30 p.m. as his wife hurried in. She said she had seen Ejigbadero in the neighbourhood and warned her husband that he may have come again to cause trouble. The husband agreed with his wife, saying he suspected that Ejigbadero may have come to bury charms on the farm, an all too familiar occurrences in disputes over land ownership in Yorubaland.

“It was at this point that a gunshot shattered the stillness of the night. Raji Oba fell. His wife, Sabitu Oba, was later to give evidence that she saw Ejigbadero fleeing from the scene of the crime in the company of six other persons. Raji Oba was rushed to the hospital where he was pronounced dead.

“Later that night on August 22, policemen arrested Ejigbadero in his Mushin residence. He was in the middle of a family celebration. Ramota, his young wife, who was delivered of a baby eight days earlier, was having a lavish naming ceremony with its attendant lavish party worthy of a big socialite of Ejigbadero’s social status. The party was attended by many top Nigerians including lawyers, judges, policemen, businessmen and women, socialites, top military officers and public servants. That was his alibi before the court. On the day of Raji Oba’s murder, Ejigbadero claimed he was far from the scene, attending to guests at his baby’s naming ceremony.

“Evidence presented to court was convincing enough, including that of policemen who saw Ejigbadero at Alimosho on the night of the murder. Some other villagers also gave evidence insisting that Ejigbadero came to Alimosho that night in the company of others in a Peugeot 504 station wagon.

“One Kehinde, one of the prosecution witnesses, gave evidence before the court. He said he was a security guard at Ejigbadero’s factory premises at Matori. He said on the night of the murder, the accused took time off from his naming ceremony, to visit the factory in the company of six other persons who were well-known to Kehinde. He named the six of them. He said they left the factory premises in a white Peugeot 504 station wagon and returned in the night around 9pm.

“The defence, led in evidence by Chief Sobo Sowemimo, made great effort to cast doubt on the testimonies of the prosecution witnesses. They also called witnesses to support their alibi that Ejigbadero never left his naming ceremony on that day. They called witnesses but not one of them was with Ejigbadero throughout the day. From the evidence presented before me, I had no doubt in arriving at my verdict that Ejigbadero was our man and that he committed the cold-blooded murder. He was guilty and sentenced to death.

“He appealed my judgement, but the Federal Court of Appeal in 1977 affirmed the judgement. The appeal was heard by Their Lordships Mamman Nasir, Adetunji Ogunkeye and Ijoma Aseme. Dissatistfied, Ejigbadero moved to the Supreme Court and a panel of Their Lordships Alexander, Fatai-Willimans, Irikefe, Bello and Idigbe, affirmed my judgement. The death sentence on Ejigbadero was carried out in 1979.

“The Ejigbadero case was sensational and became of national interest. It highlighted the human aspect of the chaotic land laws in Nigeria, especially in Lagos and its environs and its attendant capacity to disrupt and even destroy the lives of ordinary people”.

Justice Isiaka Isola-Oluwa was born on June 23, 1918 to Lagosian parents in Cross River State.

He attended Forcados Government School, Bonny; St Bartholomew’s School, Degema; Government School, Sapele; and King’s College, Lagos.

Justice Oluwa also attended School of Agriculture, Samaru-Zaria, University of London where he studied Law, and Lincoln’s Inn, London, where he was called to the Bar in 1957.

The late jurist worked severally as lecturer, Farm Management, University of Ibadan (1949-50), Lecturer, School of Agriculture, Samaru-Zaria, and Extension Manager, Zaria Province.

He started his law practice after he returned back to Nigeria from London and formed Oluwa, Kotoye and Co.

He was appointed High Court judge on June 1, 1974 and he retired on June 17, 1983.