Between January and July alone, Nigeria recorded nearly 23,000 cholera cases and 526 casualties. This represents a frightening mortality rate of almost 2.2%. What this means is that one in every 46 positive cases have died.

Compared to the coronavirus in the country, cholera is far more lethal. Even at its peak last year, the contagion had a mortality of slightly under 2%. At this pace, the diarrhoeal disease could potentially become a national catastrophe, especially as the August rainfall beckons.

While most countries battle to rebuild their economy and public health system to contain the threat of the third wave of the deadly COVID-19 pandemic, health officials in Nigeria are jolted by the resurgence of cholera. The disease, which is infamous for killing infected persons within hours if not promptly treated, is endemic in the country, resurfacing at will after it was first detected in the 70s.

The Federal Ministry of Health reported 37,289 cases and 1,434 deaths between January and October 2010, while a total of 22,797 cases of cholera with 728 deaths and a case-fatality rate of 3.2% were recorded in 2011. Outbreaks were also recorded in 2018 with the Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (NCDC) reporting 42,466 suspected cases including 830 deaths with a case fatality rate of 1.95% from 20 out of 36 States from the beginning of 2018 to October 2018.

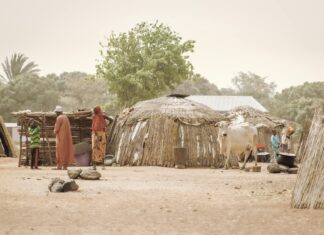

According to the World Health Organisation, cholera is an acute diarrheal infection caused by ingestion of food or water contaminated with the bacterium vibrio cholera. The bacterium is transmitted mainly through the faecal-oral, that is, by the ingestion of contaminated food or water. Its transmission is closely linked to a lack of access to clean water and poor sanitary habits.

Cholera has been described as a “disease of poverty” because social risk factors play significant roles in its transmission. Lack of access to safe drinking water and poor personal and environmental hygiene are basic to promote the spread. Infection also occurs when people eat or drink something that’s already contaminated by the bacteria. Evidence from the 1995-1996 outbreak in Kano state revealed that poor hand hygiene before meals and vended water played a role. Population congestion is another factor.

Its symptoms vary from nausea and vomiting, dehydration, which can lead to shock, kidney injury and sudden death, the passage of profuse pale, milky and watery stool (rice water-coloured) to body weakness. It can also be accompanied by intense thirst and a decrease in urine quantity, with or without abdominal pain, and with or without fever.

The NCDC reports that the Federal Capital Territory and 16 states have been the worst hit. The states are Benue, Delta, Zamfara, Gombe, Bayelsa, Kogi, Sokoto, Bauchi, Kano, Kaduna, Plateau, Kebbi, Cross River, Niger and Nasarawa.

According to the NCDC, the majority of affected people can be treated successfully through prompt administration of oral rehydration solution (ORS). It noted that severely dehydrated patients are at risk of shock and require the rapid administration of intravenous fluids. “Such patients should also be given appropriate antibiotics to diminish the duration of diarrhoea, reduce the volume of rehydration fluids needed, and shorten the amount and duration of V. cholerae excretion in their stool,” the health agency advised.

On its part, the disease centre has activated a multi-sectoral National Cholera Emergency Operations Centre (EOC) across the country to support states to ensure a coordinated, rapid and effective response to the ongoing outbreak. This includes the deployment of National Rapid Response Teams (RRT) to support the response at the state level, provision of medical and laboratory supplies, scale-up of risk communications amongst other activities.

Additionally, the resources that have been developed as part of Nigeria’s COVID-19 response are being used to strengthen the response to the cholera outbreak. This includes the digitalisation of the national surveillance system, establishment of laboratories and treatment centres, training of health workers among others.

Still, good personal hygiene can not be over-emphasised. Proper disposal of sewage and refuse, good hand washing practices and consumption of safe water and food. Nigerians must avoid open defecation and indiscriminate refuse dumping and visit a health facility immediately if they have symptoms such as watery diarrhoea.

But both the state and federal governments must make do more. They must make safe drinking water accessible to all Nigerians. They must as much as possible decongest the IDP camps across the nation. Introduction of routine sanitation, surveillance as well as community engagement should be employed to raise awareness and promote good hygiene practices. Regular health education during and after outbreaks is necessary.