Kaftan Post News Analysis

By Stephen Adewale

Thursday’s coup in Sudan may have seen the overthrow of Omar al-Bashir but the chain of crises that eventually swept the unpopular president out of office, after 30 years rule, are not going to be abated soon. A day after leading a coup that toppled the long-time leader, Defence Minister Awad Ibn Auf stood down as the head of Sudan’s military council. The new man in charge is Lt-General Abdel Fattah Abdelrahman Burhan who is regarded as a less controversial man with cleaner record than other Sudanese generals.

The level of relief displayed by continental and international actors upon al-Bashir’s exit is understandable as his story is the story of one man in one country whose action or inaction impacts on the African continent at large.

For thirty years he lasted in power, the elusive peace in Bashir’s country did not only affect the 40 million inhabitants of both North and South Sudan, the conflict in Sudan is also responsible for the turmoil in nearly all the neighbouring states in Libya, Chad, Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of Congo, Uganda, Kenya, Ethiopia, Eritrea and Egypt. Sudan’s problems are also linked to the ferment and tumult in the Maghreb and elsewhere in the Arab world, and it is connected to the incessant war in Somalia. Sudan’s ethnic and religious wars have infected Mali and Nigeria. The so-called ungovernable spaces of the Sahel and Sahara as well as the Horn of Africa are all potential breeding grounds for Isis, Boko Haram and their franchises that have spread from the badlands of Afghanistan and Pakistan to Yemen and now much of northern Africa, from Algeria to Zanzibar. Whether Bashir’s ouster from power after thirty years of iron rule contains or incites the crises remains a moot point.

President Omar al-Bashir has been one of Africa’s and, arguably, Arabia’s most controversial leaders. He was the first sitting head of state to be issued an arrest warrant, for war crimes, by the International Criminal Court. He has been a central personality in Islamic and African politics, as well as a love-to-hate figure for the US in the ‘war on terror’. With his 2014 headline role as a peacemaker in the southern civil war and other regional conflicts, Britain’s threats of a war crimes indictment by the ICC, al-Bashir’s salience became much greater.

He was a field marshal who fought and commanded in possibly the world’s longest conflict. No authoritative biography has been written on him but it is impossible to understand al-Bashir’s extended rule without detailed explanation of what transpired in Sudan before he ascended power in 1989. Indeed, without the knowledge of the previous history of ungovernability in Sudan, al-Bashir’s behaviour makes far less sense.

GENESIS OF SUDANESE CRISIS

A former American President, Jimmy Carter once famously referred to the 1953 overthrow of Muhammad Musaddiq’s elected government in Iran as ‘ancient history’ which by definition should not motivate current political attitudes. Yet, what outsiders have forgotten, or never knew, constitutes the lived experience that motivates the actors in Sudan’s conflicts.

Sudan occupied a pivotal, if initially largely accidental, role in British imperial history. For centuries it was a backwater ruled by the far-away Ottoman sultans. The 1869 opening of the Suez Canal, a lifeline to the British Raj, subsequently resulted in the de facto occupation of Egypt. Technically, Sudan became an Anglo-Egyptian colony, but it was still a backwater. Its security was a concern to the British because it was the hinterland of Egypt and because of its precious Nile waters. It was also part of the pink corridor on the imperial map, which linked it to the settler colonies of Uganda and Kenya, and the long-held ambition of a Cape-to-Cairo railway.

The Mahdi rebellion of the 1880s led to the major imperial embarrassment of General ‘Chinese’ Gordon’s death in Khartoum. To avenge this humiliation and, as ever, to deter the French, Sudan was reconquered a decade later. The British held sway until independence in 1956, although London ran Sudan with a fairly light touch. The colonialists concentrated on the Muslim-Arab triangle around Khartoum, regarded Darfur as a security problem, and dithered about the role of the Christian south, which was inhabited largely by African ethnic nationalities, ethnically and culturally distinct from the north.

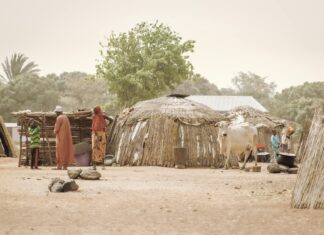

Sudan is a beautiful country indeed. A visitor would be entranced by her desert landscapes, the lushness of the deep south, the sunsets on the Nile, the ancient history of the country, the pyramids and the archaeological sites. With a landmass of 1,886,068 square kilometres (728,215 square miles), it is the third largest country in Africa. One language profile which categorised languages according to the number of speakers, identified Arabic and Dinka as the two major languages, followed by fourteen minor languages, divided into some 100 dialects. Of these nearly half are found within the Southern Sudan, representing one-third of the country’s population, residing within a quarter of its territory: while more than half are found spread throughout the remaining northern three quarters of the country.

Sudan’s history has witnessed a tragic recycling of repetitive themes. The genesis of the conflict could be traced back to 1820 when an Egyptian ruler, Muhammad Ali, invaded Sudan with the intention to acquire the Sudanese gold. To ensure maximum subjugation of the invaded territory, a religious divide was imposed on the country which was not in inspiration or intention, religious. With the structure of the Egyptian empire, Muslims among the indigenous population benefitted more than non-Muslims, and Muslim subjects could pass on their losses to non-Muslims on the margins.

The Mahdist state which overthrew the Turco-Egyptian regime and ruled between 1883-98 built on this pattern. The point advanced here, then, is that the origins of the Sudan’s current problems predate the unequal legacy of the colonial system in the twentieth century or the Bashir’s oppressive regime of the twenty-first century. The problems were embedded in the ideas of legitimate power and governance developed in the Sudanic states of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, which were incorporated into the structure of the Turco-Egyptian empire, achieved new force in the jihad state of the Mahdiyya, and were never fully replaced, but rather adapted by the twentieth century colonial state. The British favoured the riverine Arabs, while treating Darfur as a distant and occasional security problem, and failed to make any real decision on the south. The imperial rulers could have created a southern independent non-Muslim state in an informal federation with the British colonies of Uganda and Kenya. Not without its pitfalls as a solution, true, but it probably would have saved millions of lives.

When the Sudanese nationalists took over in 1956, they practiced roughly the same policies as their colonial predecessors: centralised authoritarian rule, while ignoring the peripheries. Unlike the British, the new government in Khartoum enforced Islamisation and Arabisation in the south, which was bound to cause perpetual conflict. The new Sudanese leaders ironically copied much of the political and economic practices of the departed British, although the tone in Khartoum was of course more Islamic.

Upon taking over in 1989, al-Bashir’s Sudan became a major oil exporter, and this sucked in international players hungry for mineral resources. China became the dominant influence, which helped to displace Western interests. Western economic sanctions also meant that Beijing had a freer hand. Osama bin Laden was a guest of al-Bashir’s government from 1991 to 1996, perhaps not the best way to win friends in the US. Sudan became listed as a terrorist state and was embroiled in the American ‘war on terror’ after the 9/11 abominations. Khartoum thought that, after Afghanistan and Iraq, it was to be next in line for regime-change treatment. The US stepped up its support for the southern rebels while American lobby groups, and Hollywood stars, became active in the anti-Khartoum movement after ‘genocide’ was declared in Darfur.

Nevertheless, al-Bashir later became an ally of the US, Britain, Norway and African states such as Kenya to conclude the Comprehensive Peace Agreement signed at Naivasha, Kenya, in January 2005. Despite US sanctions, al-Bashir was hailed as a peacemaker. The media firestorm over the savagery, on various sides, in the Darfur war, however, led to the denunciation of al-Bashir as a war criminal, and indictments at the International Criminal Court. Sudan was once more considered a rogue state in much of the West, although the European Union dropped its sanctions.

Al-Bashir’s team largely played according to the rules of the 2005 agreement, with an uneasy southern-northern government of national unity in Khartoum, reasonably free elections in 2010, and finally the referendum in 2011 in the south that led to an overwhelming vote for independence. With hindsight, imperial Britain should have grasped the nettle and allowed the south its separate existence after 1945. Many southern leaders, most notably the charismatic but autocratic leader of the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA), Colonel John Garang de Mabior, hoped to create a united Sudan with the democratic participation of the south, west and east, of what was Africa’s biggest country. After Garang’s death, just after the signing of the 2005 deal, the southern leadership returned to the preferred option of independence.

When South Sudan emerged as Africa’s newest state in the summer of 2011, many outside observers hoped that the main fault-line and cause of Sudan’s wars could be resolved. Instead, the south – umbilically connected to the economy of the north – dissolved into ethnic civil war. By 2014 the traditional enemy, al-Bashir, was brought in by the southern president, Salva Kiir, to help forge peace, aided by the neighbouring states. By then, the southern war had emasculated the two countries’ oil supplies. South Sudan, already a failed state, slipped into famine and disaster.

The north endured riots because of increases in food prices and other staples. A military-intelligence coup almost brought down al-Bashir. He had come to power in a putsch, but now survived one that aimed to topple him. By early 2014 al-Bashir’s family members were unanimous in pleading for him to step down. He had been in the army for thirty-nine years and President for twenty-five years. Many in the ruling National Congress Party wanted a new face, but the old guard felt al-Bashir should run again in the scheduled 2015 elections. Eventually, he listened to the latter and stood for the election which he won in 2015. The end eventually came on Thursday as he was toppled following months of unrest over the cost of living.

From 1989 to 2019, reemerging in the al-Bashir’s Sudan was the exploitative nature of the central state towards its rich, but uncontrolled hinterland. Resurfacing was the coercive power of the army in economic as well as political matters. Reappearing was the prerogative of the leader in redistributing revenues to the peripheries, and the ambiguous status of the citizens who are not fully part of the central heritage.

This diversity and other historical factors such as religion, local perceptions of race and social status, economic exploitation, colonial and post-colonial interventions which led to the emergence of al-Bashir’s emergence in 1989 and eventually led to his forceful exit are being left unaddressed by the new Sudanese leaders who seized power from al-Bashir. Within two days of being in power, these factors have received a further impetus from the new Sudan leaders with their clear distinction between people with and without full legal rights.

ONE STEP FORWARD AND TWO STEPS BACK IN SUDAN

Sudan entered the post al-Bashir era mired in not one, but many crises. What had been seen in the 1980s as a crisis between North and South, Muslim against Christian, Arab against African, has, after nearly four decades of hostilities, broken the bounds of any North-South conflict. Fighting has spread into theatres outside the southern Sudan and beyond the Sudan’s borders. Not only are Muslims now fighting Muslims, but ‘Africans’ are fighting ‘Africans’.

A war once described as being fought over scarce resources is now being waged for the total control of abundant oil reserves. The fact that the overall civil war, which is composed of these interlocking struggles, has continued for so long, far outlasting the international and regional political configurations which at one time seemed to direct and define it, is testimony to the intractability of the underlying causes of the conflict. Lasting peace will be achieved only through addressing the root causes of the Sudanese crisis, but there must be political will among the relevant stakeholders to address those root causes.

Corruption, which had become rampant and blatant in Khartoum deserves speedy attention. At a point, it was discovered that government payments were being made to individual cows! Although many of the wonderful lyre horned cows in the country do

have their own names, the money was intended for humans. Many members of al-Bashir cabinet members felt a sense of entitlement and after 30 years in power, the former freedom fighters had become public looters. This must stop for Sudan to make progress, but with the configuration of the new leaders who have emerged in quick succession, corruption is not likely to fade out anytime soon in Sudan.

Sudan is desperately underdeveloped. Approximately 90% of the citizens live on less than a dollar a day and half required food aid. The prime issue is still a settled border. One of the peculiarities of Sudan’s crisis is that the longer it has lasted, the greater has been the deterioration in the quality of intervention by other African countries and organisations. Disputes fester and the AU has not done any better in Sudan than it did in Zimbabwe or Ethiopia. Arguments over sharing the national debt has not been reconciled nor has citizenship issue been fully resolved.

Peaceful cooperation between the two Sudanese states make sense in the coming days. 80% of proven reserves of the Sudanese oil are in the South, but the pipelines to the sea from the landlocked south ran through northern Sudan. Talk of building alternative pipelines, through difficult terrain, to the sea via Kenya did not make sense, because of the high costs and the probability that Southern oil output would soon peak and then decline rapidly. Border disputes can spark off war by accident. Tribal clashes spawn by dissident warlords should also be expected in the days ahead.

Technically, Sudan is a rich country full of very poor people. Agricultural potential is high, but the farms and estates had been devastated by war. Statistically the country is already a failed state at the time al-Bashir dropped the ball on Thursday. As the situation was when Omar al-Bashir was in power, so it is now. But however impossible peace, progress and development may seem to be, they have not been forgotten, and they can be restored.