Katell Abiven AFP, Havana

Havana — By 11 am on a recent Saturday morning , I’ve already driven to three gas stations in Havana, without being able to find diesel. The fuel gauge of my Kia Sportage is getting lower and lower. I only have a quarter of a tank. Despite the heat, I turn off the air conditioning to save the little gas that’s left, for I don’t know when I’ll be able to fill up.

I decide to try a fourth gas station and am relieved to see that it only has a line of 20-30 vehicles outside, which means I should only be here for an hour and a half. For weeks, lines at petrol stations have been stretching to five or six hours, sometimes an entire day. Some people have actually spent several days waiting in lines at gas stations.

It all started on September 11, when Cuban President Miguel Dian-Canel went on television to explain that the island was facing a “cyclical” fuel shortage. The reason? American sanctions on ships transporting fuel from Venezuela, which is Cuba’s main supplier.

Dian-Canel assured the public that a shipment would arrive in three days and others by the end of the month. There is no reason to worry, he crooned, by the beginning of October, the situation would be back to normal.

Cubans knew better. Lines at gas stations began to form before he finished speaking. People were filling up their tanks and storage containers to stock up.

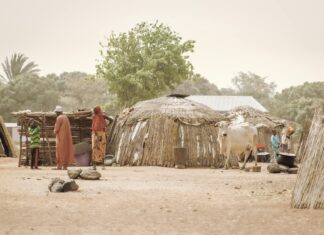

As the days passed, the lines became longer and longer and the government started to implement fuel-saving measures. Busses and trains began to run less frequently, air conditioners stopped humming, then electricity began to be shut off for a few hours every day in government buildings. In the countryside, farmers began to use horses and bulls instead of tractors.

Many Cubans remembered all too well the last time there was a prolonged shortage of fuel. It was the 1990s and the Soviet Union had just crumbled. The fuel that the Soviets provided to its client state dried up and the same measures were applied.

Cubans came to call this slice of their history as “the special period,” an expression that remains painful for a population that hasn’t forgotten the hunger, the disease and the lack of hope that pushed 45,000 people to leave the island.

In the year that I have lived in Cuba, I have gotten used to shortages that are part of life on this island, which has been under US embargo since 1962, following the Cuban Missile Crisis. Normally a single product disappears from shelves — since I’ve been here we’ve spent several weeks without flour, then chicken vanished, then you couldn’t find butter and bottled water.

Faced with these unexpected shortages, people organize. In recent years, technology has made this much easier. For several years now there have been WhatsApp groups that exchange information on what can be found where. Often these groups have hundreds of members and waiting lists. I myself am a member of six different such groups — some exchange information of what’s available at which supermarket, others are go-betweens individual people selling wares.

Until recently, Cuba was one of the least-connected countries in the world. Its Internet was limited to paid wifi access in certain public places, so the use of the chat groups wasn’t widespread. But when 3G arrived on the island last December, it was like an earthquake and the use of the groups exploded, even though the costs of Internet remain quite high compared to average salaries.

“Hello group, do you know where I can find bottled water?” “Has anyone seen beer?” “Toilet paper?” Such messages appear on my smartphone every day. Sometimes I answer, sometimes I pose the question. Amazingly, someone nearly always answers queries. There is also a host of groups on Russian-developed Telegram, which is reputed to be more secure than US-developed WhatsApp.

The day after the president’s televised address, a dozen groups dedicated to the fuel shortage were already up and running to answer the question of the day “Donde hay combustible?” (Where is there fuel?) Some groups are specialized in unleaded or diesel, since the shortage has come in waves — the first week it was unleaded and super that vanished, the following weeks diesel disappeared.

Everyone in my social circle has been affected. I have friends who had waited nearly 24 hours in front of a gas station that was due to receive a shipment, watching television shows on their tablets to pass the time. My husband left the house one Sunday morning in search of super…. to return five hours later, albeit victorious. He had waited in line for five hours before the gas station attendant announced that they had run out. He dashed to another station, and even though he was far from the only one there, he managed to fill up the tank. My nanny told me that she once saw a truck driver brushing his teeth next to his vehicle in front of a gas station — he had been there for several days.

When the shortages first started, an ambiance of humour reigned in the chat groups, which include a lot of taxi drivers. “Where is there fuel?” “In Venezuela!” But as the days dragged on and the shortages became more painful, people who try these types of jokes risk being banished from the group.

The taxi drivers seem especially worried — logical since their livelihoods are directly affected. “I have friends who have spent four days in front of a station,” writes one. Another says he has spent a week in line. A third says he hasn’t been able to work in 10 days and has spent the last two in line in front of a gas station.

A lot of people stand in line without being sure if the station is even going to get gas, since rumors run like wildfire in these conditions. “They’re saying they’re going to get shipments soon,” writes one person. “Apparently there won’t be any diesel anywhere until September 30,” writes another. Some are furious to have used up their remaining gas to get to a station that was supposed to have received a shipment…. only to find that there is none.

In the line where I find myself on this particular Sunday morning, I talk to a truck driver who has been in the business for 30 years. He tries to look at the situation philosophically. “All of this is politics, so there is nothing that we can do. But each time it’s us, the people, who suffer.” The US says its sanctions aim are aimed at the Cuban government, which it accuses of supporting the one of Venezuela’s Nicolas Maduro. But it’s the Cuban population that’s feeling the effects of this policy the most.

When I speak to a doctor whom we are due to interview soon for a story, she tells me that since there are no longer buses in her neighborhood, she has to walk up to 40 minutes to get to the hospital where she works. She says this in a calm manner, as if she is telling me something banal. It makes me realize just how lucky I am to be a foreigner in this country — not only do I have a car, but I can also afford the luxury of leaving it at home and taking a taxi to work, like I’ve done all week. Most Cubans don’t have this luxury — most of them don’t even own a car and make do between buses and hitchhiking.

There is a lot of resignation, with Cubans saying that they have been perpetually “en lucha” (“in a struggle”) since the Cuban Revolution in 1959 that put the socialists that eventually turned communist in power. As the economic difficulties mount, the government tells its people to live through this “different normality” by tightening their belts a bit more.

After about a month, the fuel shortage has eased. Drivers can now easily find it. But few are letting their guard down. As a user on one of my chat groups wrote “Let’s hope it lasts.”